Years ago, in a staff Secret Santa, I was given a framed quote from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra:

‘One must have chaos in oneself to give birth to a dancing star.’ (1885/2003, p.46)

It still hangs above my desk. I’ve always found the line both unsettling and inspiring – a reminder that creation, whether artistic or pedagogical, demands a certain interior tumult, a willingness to dwell in uncertainty and still make something incredible from it.

That small gift comes to mind whenever I think about what we call effective teaching. In contemporary education, the term is often tethered to ‘evidence-based practice’ and the ‘what works’ policy agenda. We are urged to trust insights from scientific experiments, randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses – as if teaching were something that could be reduced to laboratory findings (Wrigley, 2019). Yet this reduction is not neutral – it carries with it a genealogy, a hidden moral story about what counts as ‘good teaching,’ ‘best practice’ and the ‘truth’ about learning.

Furthermore, within this genealogy, less certain terms once considered part of a teachers’ skill set, such as intuition, creativity and engagement, are often seen as naughty words; best avoided, sometimes taboo. Alternative paradigms of pedagogy are also silenced – philosophical, constructivist and critical pedagogies are often bypassed by writers with little holistic understanding of the ontological and epistemological nuances of evidence and research.

To see this, we might borrow Nietzsche’s method from On the Genealogy of Morals (1887/1989). Nietzsche warns that our moral categories – good, evil, useful, virtuous – are not eternal truths. They are layered inheritances, historically contingent and often rooted in the social need to make life predictable and governable. What we call ‘good’ – or, perhaps, ‘outstanding’ or ‘effective’ – is, for Nietzsche, a palimpsest of older struggles: the taming of instinct, the codification of vitality into rules.

So too in education. The idea that effective teaching is that which conforms to evidence-based protocols may appear self-evident, but it has its own genealogy. It descends not from the lived wisdom of classrooms, nor from the deep craft traditions of pedagogy, but from a managerial and technocratic turn in schooling: an insistence that learning outcomes be measurable, interventions be replicable and teachers be interchangeable technicians rather than singular beings (Ball, 2003; 2021).

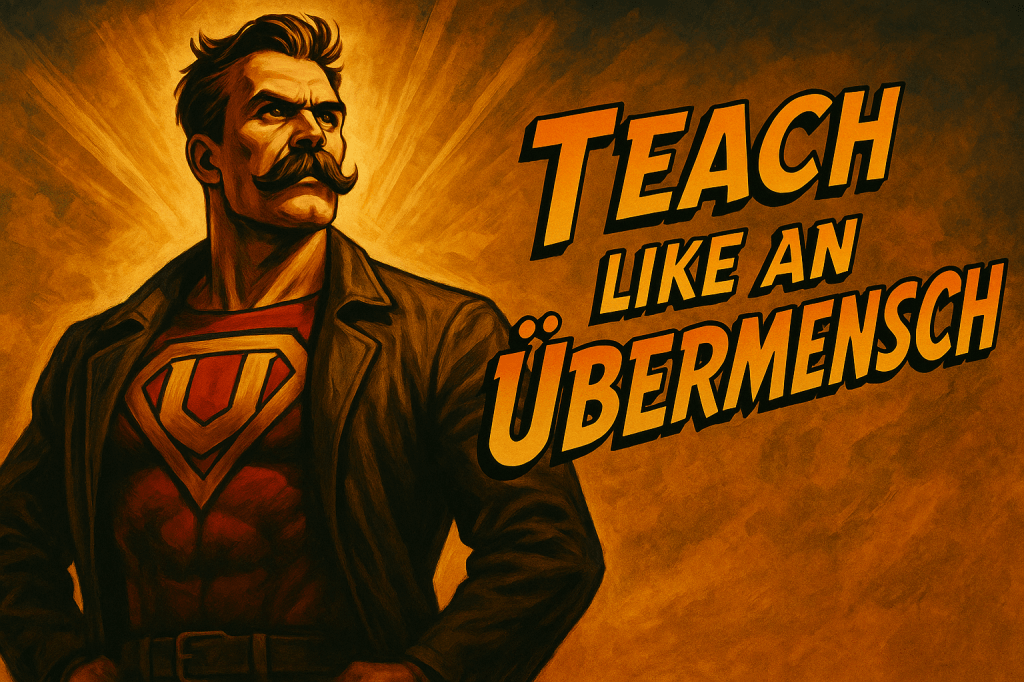

Here the figure of the Übermensch-teacher — not a ‘superhuman,’ but a metaphor for the teacher who continually recreates their values and practice – becomes a curious, perhaps even legendary, presence: the teacher we remember as inspiring us; the teacher our pupils say they want to see; the idealised figure of the pedagogue invoked by parents, politicians and popular culture alike. Such teachers embody an artistry that slips through the net of randomised controlled trials. They are not good in the sense of obedient or compliant, but excellent in the older, Nietzschean sense of overflowing vitality, creative improvisation and the capacity to shape the moral atmosphere of a classroom.

This includes Miss Honey, Mr Keating, Mr Braithwaite and Miss Watson, among many others who inhabit our collective imagination – as well as Mrs Fellows, Mr Strange and Mrs Jarvis from my own memories. And, of course, there are a few among my colleagues too.

Nietzsche’s challenge was always to move beyond reactive moralities: systems that define the good only as the avoidance of error. Evidence-based orthodoxy risks exactly this – a pedagogy of compliance rather than creation. The Übermensch-teacher acts differently: not lawless, but self-legislating; not reckless, but responsive to the living moment rather than to the pre-approved script.

To argue for effective teachers as Übermenschen is not to reject evidence outright, but to situate it within a larger genealogy. Evidence tells us something, but never everything. It describes tendencies, not essences; it offers probabilities, not singular acts. Teaching, however, is always singular – always occurring in the encounter between this teacher, this class, this child. The artistry of teaching resists total capture.

The danger of forgetting this genealogy is that we mistake a contingent definition of effective teaching for an eternal one. We risk chaining teachers to practices that are ‘proven’ in abstract but deadening in the living classroom. Nietzsche would urge us instead to recover older, more vital notions of excellence: teachers who are not technicians but creators, not appliers of technique but Übermenschen – male and female workers of spirit, transformers of worlds.

In the end, perhaps the question is not whether teaching is evidence-based, but whether it is life-affirming. A truly effective teacher is not the one who ticks the boxes of the latest meta-study, but the one who, like the Übermensch-teacher, shapes human becoming in ways that escape our instruments of measurement.

And as I look at that framed line – ‘One must have chaos in oneself to give birth to a dancing star’ – I sometimes wonder why that was the quote chosen for me. Did my Secret Santa see something in my teaching that I couldn’t? Does it say something about the kind of teacher I am – or the kind I hope to be? Or am I simply deluded?

References

Ball, S.J. (2010). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

Ball, S.J. (2021) The education debate (4th ed.). Policy Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1883–85/2003) Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None. Translated by R. J. Hollingdale. London: Penguin Classics.

Nietzsche, F. (1887/1989) On the Genealogy of Morals. Translated by W. Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale. New York: Vintage Books.

Wrigley, T. (2019). The problem of reductionism in educational theory: Complexity, causality, values. Power and Education, 11(2), 145-162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757743819845121