This brief blog draws on insights from my doctoral research and highlights my frustration with the current narrow interpretations of ‘evidence-based practice’ and ‘evidence-informed practice,’ which often overlook the richness and diversity of educational research paradigms.

While these terms are similar, it is worth noting that evidence-informed practice recognises that students, teacher expertise and school context significantly influence the application of research in the classroom (Neelen and Kirschner, 2020).

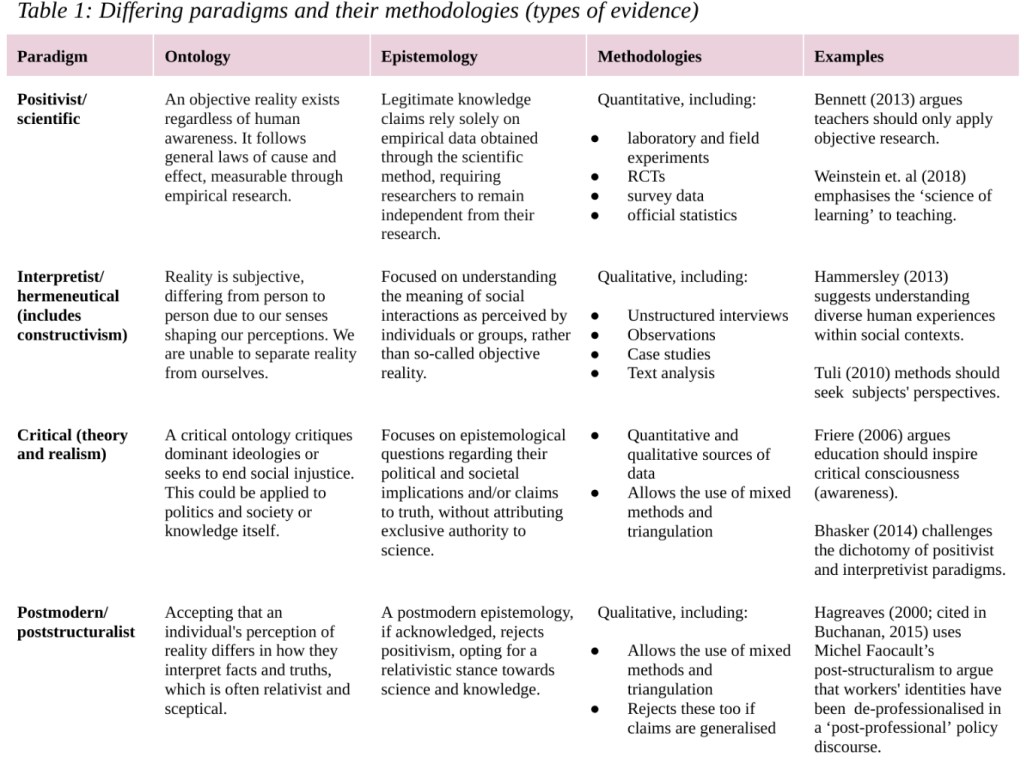

In discussions about evidence-based practice and evidence-inform practice in education, the term ‘evidence’ often becomes narrowly defined, favouring scientific or positivist methodologies. However, the concept of evidence is far more nuanced, encompassing a rich spectrum of research paradigms, each offering unique insights. Understanding these paradigms is essential for policymakers, educators and researchers aiming for a holistic view of evidence in education.

Historically, educational research has oscillated between quantitative (positivist) and qualitative (interpretivist) approaches. Positivism, rooted in the belief in an objective reality, emphasises empirical research methods such as laboratory experiments, randomised control trials and surveys. Writers like Bennett (2013) and academics such as Weinstein et al. (2018) advocate for the application of such objective findings in teaching, emphasising the ‘science of learning.’

Conversely, interpretivist and hermeneutic paradigms focus on subjective realities shaped by individual perceptions. Methods like semi and unstructured interviews, case studies and observations aim to understand social interactions within specific contexts. For instance, Hammersley (2013) emphasises the importance of capturing diverse human experiences, while Tuli (2010) underscores the need to consider participants’ perspectives.

Critiques of the positivist-interpretivist dichotomy have led to the emergence of integrative paradigms. Critical realism, as advocated by Bhasker (2014), combines qualitative and quantitative methods to explore causal mechanisms behind observed phenomena. Similarly, poststructuralist and postmodern approaches challenge traditional epistemologies, embracing qualitative triangulation and practitioner narratives to address issues of power, ideology and social justice (Hargreaves 2000; Buchanan, 2015; Ball, 2021).

Likewise, other commentators suggest complexity theory, mixed methods or critical theory as ways to bridge this epistemological schism (Mason, 2008; Sammons and Davis, 2017; Wulf, 2003). Unlike demarcated positivist and interpretivist paradigms, these approaches can be viewed as interdisciplinary in terms of methodologies and the utilisation of evidence.

The table below, which I put together to help me with my doctoral research, outlines these differing paradigms, their ontological and epistemological foundations, methodologies, and examples:

Ultimately, navigating these paradigms requires embracing their diversity. Policymakers and educators must resist the temptation to prioritise one form of evidence over others, opting instead for an interdisciplinary approach to foster a nuanced, equitable understanding of educational practices.

Further reading

Jones, A. (2024). ‘Rethinking Evidence-Based Practice in Education: A Critical Literature Review of the ‘What Works’ Approach.’ International Journal of Educational Researchers, 15(2), 37-51.

References

Ball, S. J. (2021). The Education Debate (4th ed.). Bristol: Policy Press.

Bennett, T. (2013). Teacher proof: Why research in education doesn’t always mean what it claims, and what you can do about it. London: Routledge.

Bhasker, R. (2014). The possibility of naturalism: A philosophical critique of the contemporary human sciences. London: Routledge.

Buchanan, R. (2015). ‘Teacher identity and agency in an era of accountability.’ Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), pp. 700–719.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. London: Routledge.

Freire, P. (2006). Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Penguin Classics.

Hammersley, M. (2013). The myth of research-based policy and practice. London: SAGE Publications.

Mason, Mark (2008). Complexity theory and the philosophy of education. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Neelen, M. and Kirschner, P.A. (2020). Evidence-informed learning design: Creating training to improve performance. London: Kogan Page.

Sammons, P. and Davis, S. (2017). ‘Mixed methods approaches and their application in educational research,’ In Wyse, D., Selwyn, N., Smith, E. and Suter, L.E. (eds.), The BERA/Sage Handbook of Educational Research Volume 1, 477-504. London: Sage Publications.

Tikly, L. (2015). ‘What works, for whom, and in what circumstances? Towards a critical realist understanding of learning in international and comparative education’, International Journal of Educational Development, 40, 237–249.

Tuli, F. (2010). ‘The basis of distinction between qualitative and quantitative research in social science: Reflection on ontological, epistemological, and methodological perspectives.’ Ethiopian Journal of Education and Sciences, 6(1), 97–108.

Weinstein, Y., Madan, C. R., & Sumeracki, M. A. (2018). ‘Teaching the science of learning.’ Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 3(1), 2.

Wulf, C. (2003) ‘Educational Science – Hermeneutics, Empirical Research, Critical Theory’, European Studies in Education, 18.

Hargreaves, A. (2000). ‘Four ages of professionalism and professional learning.’ Teachers and Teaching, 6(2), 151–182.

Picture credit: Picpedia.org (Used under a Creative Commons Licence)