In contemporary education policy, teacher development programmes and popular notions of ‘best practice,’ the rise of the ‘science of learning’ and the broader ‘what works’ policy agenda is often presented as an unequivocal good. Here, evidence-based practice promises to elevate teaching from intuition to precision, replacing professional judgement with universal principles derived from cognitive science, behavioural research and large-scale trials.

Yet beneath this technocratic confidence lies a deeper epistemic tension. Much of this movement is driven by what can be called epiphenomenal empiricism – the assumption that only observable correlations, behavioural outcomes or measurable interventions constitute legitimate educational knowledge.

Whilst the term itself is not widely used or standardised in academic literature, it captures a critique of positivist social science long articulated within realist social theory, particularly in the work of social theorist and sociologist Margaret Archer (1995, 2000). For Archer, empiricist traditions frequently collapse social reality into its empirical dimension – what is readily seen or measured – whilst ignoring, or at least underplaying, the structural, cultural and agential mechanisms that generate those observations. This produces what she famously calls downwards conflation: the reduction – and, arguably, simplification – of complex social processes to surface-level regularities.

When applied to education, epiphenomenal empiricism encourages policymakers and researchers – particularly those invested in the cognitive sciences – as well as edu-influencer-style consultants, to treat the effects of experiments or meta-analyses as if they were explanations for why things actually happen. For instance, a controlled intervention that improves recall on a lab-based task often becomes a decontextualised prescription for classroom teaching, with minimal attention to institutional constraints, teacher agency or student diversity in the processes described.

An example of the above is arguably seen in the promotion of interleaving: a strategy that may show promise in improving pupil attainment, but whose strongest advocates often cite little – or at least very limited – classroom-based evidence to justify its widespread application (see, for example, Bjork & Bjork, 2019, who advocate for interleaving in British schools despite drawing on very little evidence from primary or secondary age learners; see also Jones, 2023, for my own admittedly questionable – yet peer-reviewed – attempt to exemplify their ideas in the classroom).

The impressive quantitative veneer in many science-centric studies, think pieces and popular education books masks the fact that education is not a closed system; the underlying causal mechanisms of empirical phenomena rarely operate uniformly across contexts. Interleaving, for example, may work well in some situations more than others. Moreover, how teachers interpret the idea, understand the research and evaluate its effectiveness needs to be factored into any wider justification for its roll-out within a particular classroom, school or trust – as well as how it is implemented, how it corresponds to the structure of exam syllabuses and papers and, of course, what is interleaved, when and how. And that is before we even consider our pupils’ reactions to it. Hardly any of this is addressed in cognitive-science-based papers, blogs or social media posts that suggest teachers should adopt it as a strategy.

Furthermore, in response to the shortcomings of epiphenomenal empiricism, Archer’s morphogenetic approach to social realism insists that educational outcomes emerge from interactions between structure, culture and agency – interactions that cannot be reduced to experimental data or empirical evidence alone. The nature, context and impact of these interactions should be considered by classroom teachers, school leaders and policymakers before jumping on the next ‘evidence-based’ bandwagon without caution. This might help avoid what cognitive scientists call ‘mutations,’ which rarely involve any reflection on how advocates of the ‘science of learning’ – who now bemoan these mutations – may have contributed to them through their eagerness to promote ‘what works’ in the first place. Here, giving due weight to other types of research, including context-specific case studies that may involve qualitative methodologies, alongside a more critical stance, may be beneficial in triangulating what works, for whom and under what context-specific conditions. For critical (or social) realists like Archer, this acknowledges the underlying institutional cultures or agentic reactions that may hinder or even empower the smooth running of effective teaching strategies and interventions.

Subsequently, the ‘what works’ policy agenda and popular notions of evidence-based practice risk reifying contingent findings as universal truths. They privilege positivist paradigms of reality that assume school leaders and classroom teachers are implementers of learning rather than reflexive agents. They also promote a narrow hierarchy of evidence in which laboratory experiments, which do not occur in the reality of classrooms, and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) sit atop a pyramid that excludes valuable interpretive and critical scholarship (Biesta, 2010). In doing so, they foster a depoliticised vision of schooling: social inequality, unobservable institutional structures and histories, and far less tangible socio-cultural meanings appear only as background noise to be controlled for.

Importantly – and to any cognitive scientists or evidence-based practitioners who have read this far – this critical stance does not reject empirical research (I am very much in favour of it and consider it central to our understanding of learning, including the work of the Bjorks, which has undoubtedly influenced my classroom practice for the better). Rather, it challenges the epistemic reduction that occurs when empirical correlations bypass, or in some situations are mistaken for, causal mechanisms or normative structures that cannot be observed in experiments or accounted for in meta-analyses.

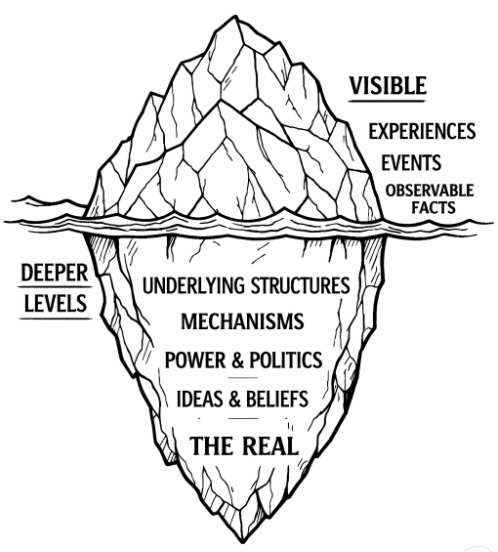

A more robust science of education, therefore, would arguably adopt a stratified ontology – recognising that what is visible is often only the tip of a deeper causal iceberg, an analogy critical realists are fond of (see Fletcher, 2017 and the adapted illustration below). Such a perspective aligns more closely with Archer’s realist critique and invites a broader methodological pluralism that honours the interpretive, relational and moral dimensions of teaching. Here, Archer’s work follows – and resonates with – other critical realists, including philosophers of science such as Roy Bhaskar (2008) and educational theorists like David Scott (2010).

The diagram above shows how critical realism distinguishes between what we can directly observe on the surface and the deeper, often hidden structures and mechanisms that shape reality beneath it. These hidden structures are often bypassed or not fully accounted for in research that focuses solely on experiments or correlations, where the researcher has predetermined which interventions, groups or variables to compare, contrast and analyse.

As educational institutions continue to invest in evidence-based training, the danger is that epiphenomenal empiricism becomes the dominant – and unexamined – common sense of educational research. Without critical reflection on its limitations, the promise of ‘what works’ may not only obscure what matters, such as our values and reasons for teaching, but also, ultimately, obscure a fuller picture of how and why things are so in contextually complex, open and constantly changing classrooms.

References

- Archer, M. S. (1995). Realist social theory: The morphogenetic approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M. S. (2000). Being human: The problem of agency. Cambridge University Press.

- Bhaskar, R. (2008). A realist theory of science (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Biesta, G. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Routledge.

- Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2019). The myth that blocking one’s study or practice by topic or skill enhances learning. In C. Barton (Ed.), Education myths: An evidence-Informed guide for teachers. John Catt Educational Ltd.

- Fletcher, A. J. (2017). Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(2), 181–194.

- Jones, A. B. (2023). Leveraging homework for effective learning: Exploring the benefits of spaced and interleaved practice. Impact: Journal of the Chartered College of Teaching, 19.

- Scott, D. (2010). Education, epistemology and critical realism. Routledge.