In the course of writing a paper I ultimately chose not to publish, I developed a taxonomy of pedagogical paradigms – an attempt to bring some structure to the often overwhelming landscape of educational theory.

Whilst the paper itself didn’t feel ready or necessary for formal publication, I still believe the taxonomy – tabulated and non-hierarchical – has something to offer. So, I’ve significantly scaled back the original material and put together this blog to share the core ideas.

Why we need a pedagogical taxonomies

Pedagogy is not a monolith; it encompasses a wide range of paradigms, from cognitive science-based strategies to culturally responsive teaching. The term paradigm refers to a fundamental framework or worldview that shapes how researchers understand and investigate social phenomena. Yet in many education blogs, books and even research papers, authors rarely acknowledge the paradigm within which they are working. This has led many to privilege their own view of ‘what works’ over others – whether this is intentional or not, I cannot say.

Nevertheless, as educational research continues to evolve, it becomes increasingly difficult to understand how these paradigms intersect, diverge or contribute to pupil outcomes. The value of this basic tabulated taxonomy lies in its ability to categorise these diverse perspectives into a clear, accessible overview – supporting teachers and teacher-researchers in thinking about the different ways of understanding, discussing and applying pedagogy in classrooms and schools. Unlike Benjamin Bloom’s ([1956] 1984) famous – and often debated – taxonomy, this is not a hierarchical framework for classifying educational objectives by complexity.

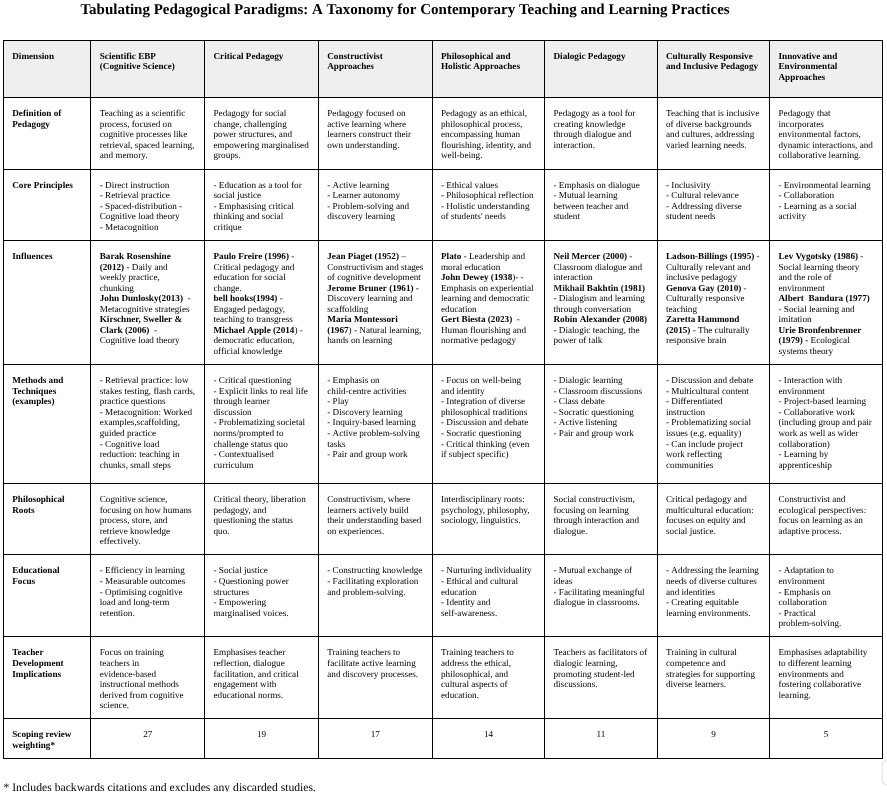

The taxonomy discussed here emerged from doctoral research aimed at understanding how evidence-based practice (EBP) influences early career teachers’ professional agency. It involved a scoping review, a systematic method for mapping key concepts in a research field (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). By identifying and categorising over 100 peer-reviewed articles, I endeavoured to classify pedagogical approaches into seven primary paradigms – each with distinct philosophical roots, instructional strategies and educational implications.

Methodological approach: The scoping review

The taxonomy was constructed through a scoping review – a method used to map the breadth of existing research without assessing its quality (Levac et al., 2010). This involved querying educational databases using keywords like ‘pedagogy,’ ‘teaching styles’ and ‘evidence-based practice,’ followed by categorising studies into shared paradigms. The findings were then tabulated based on their theoretical principles, instructional methods and implications for teacher development.

A total of 112 articles were initially identified, with 10 later discarded as duplicates or irrelevant. The final weighting was as follows:

- Scientific EBP: 27 articles

- Critical Pedagogy: 19

- Constructivist Approaches: 17

- Philosophical and Holistic: 14

- Dialogic Pedagogy: 11

- Culturally Responsive: 9

- Innovative/Environmental: 5

These weightings reflect the prevalence of each paradigm in general discourse, not their effectiveness or superiority.

The seven paradigms of teaching and learning

The taxonomy suggested here divides educational paradigms into the following categories:

- Scientific evidence-based practice (EBP)

- Critical pedagogy

- Constructivist approaches

- Philosophical and holistic approaches

- Dialogic pedagogy

- Culturally responsive pedagogy

- Innovative and environmental approaches

Each paradigm is defined not only by its teaching methods but also by its philosophical foundations, educational goals and implications for teacher development.

Here is the tabulated taxonomy. A brief explanation of each paradigm follows:

1. Scientific evidence-based practice (EBP)

Rooted in cognitive psychology, scientific evidence-based practice (EBP) prioritises techniques that improve memory, retention and cognitive efficiency. Practices such as retrieval practice, spaced repetition and cognitive load theory have been widely promoted (Rosenshine, 2012; Dunlosky et al., 2013; Sweller, 2016). Often based on laboratory experiments, field studies, randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses, proponents of scientific EBP view its research base as more rigorous than other forms of educational research. Whilst highly effective in boosting test scores and factual recall, critics argue that this approach may marginalise the social and ethical dimensions of learning, as well as qualitative studies and other types of research (Biesta, 2023; Wrigley & McCusker, 2019).

2. Critical pedagogy

Inspired by Paulo Freire and bell hooks, critical pedagogy views education as a political act. It emphasises the empowerment of marginalised communities and encourages pupils to question dominant social norms (Freire, 1996; hooks, 1994). Unlike the instrumental rationality of EBP, critical pedagogy demands that teachers become facilitators of social justice, actively engaging with questions of power, equity and identity. However, critics question the idea that pedagogy should prioritise pupils’ lived experiences and independent discovery of knowledge, arguing that this approach is inefficient and can limit the breadth and depth of learning (Christodoulou, 2014).

3. Constructivist approaches

Constructivism highlights the importance of learners actively building their own understanding through experience and reflection. Influenced by Piaget and Bruner, this paradigm favours inquiry-based learning, discovery and problem-solving (Piaget, 1952; Bruner, 1961). Whilst often contrasted with direct instruction, constructivism is not inherently at odds with scientific EBP; both have their place depending on the learning context. Some criticisms, however, include its ambiguity, potential for relativism and challenges in practical application, especially for certain learners or in specific context (Alanazi, 2016) as well as overall effectiveness (Kirschner et al., 2006).

4. Philosophical and holistic approaches

This paradigm takes a more reflective view, emphasising pupil well-being, identity and ethical development. Thinkers like Dewey and Biesta have argued that education should go beyond content delivery to nurture the whole person (Dewey, 1938; Biesta, 2023). Rather than offering specific classroom strategies, this approach encourages educators to adopt a deeply thoughtful and values-driven mindset. Nevertheless, this position drawn criticism for its potential to overemphasise philosophical concepts at the expense of practical considerations (Thompson, 2024).

5. Dialogic pedagogy

Championed by Robin Alexander and Neil Mercer, dialogic pedagogy focuses on the co-construction of knowledge through meaningful dialogue (Alexander, 2008; Mercer, 2000). It encourages teachers to create learning environments where discussion, debate and questioning are central. This approach shares common ground with both constructivism and critical pedagogy, making it a powerful tool for building collaborative and democratic classrooms. That said, challenges to this view include teachers’ ability to orchestrate effective dialogue, potential for uneven participation and the time commitment required for preparation and facilitation (Cui & Teo, 2020).

6. Culturally responsive pedagogy

Developed by scholars like Gloria Ladson-Billings and Geneva Gay, this paradigm responds to the increasing diversity of today’s classrooms (Ladson-Billings, 1995; Gay, 2010). It involves adapting teaching practices to reflect pupils’ cultural backgrounds, ensuring that all learners feel seen and respected. This approach is essential for promoting equity and inclusion, especially in multicultural societies. However, criticisms include potential tokenism, superficial application and overlooking structural inequalities (Kehl, 2024).

7. Innovative and environmental approaches

Although underrepresented in the literature, this emerging category includes environmental education, collaborative learning, and technology-enhanced instruction (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Lee & Chen, 2020). These approaches highlight the importance of real-world learning, adaptability and cross-disciplinary integration. Nonetheless, much like philosophical and holistic approaches, they can be criticised for a lack of adequate teacher training, challenges in integrating them into existing curricula, and the potential to induce feelings of helplessness or anxiety in pupils (Kiss, Köves, & Király, 2024).

Advantages of tabulated Taxonomies

A tabulated format, like the one offered here, offers several practical benefits:

- Clarity and accessibility: By presenting information in columns and rows, complex educational theories become easier to digest.

- Comparative analysis: Educators can quickly compare core principles, teaching strategies, and philosophical foundations across paradigms.

- Curriculum planning: Teachers can use the taxonomy to align their instructional strategies with specific learning goals and pupil needs.

- Interdisciplinary insights: The taxonomy encourages educators to borrow ideas across paradigms, fostering innovation and cross-pollination.

Limitations and criticisms

Despite its value, the suggested taxonomy in this blog has limitations. One concern is oversimplification. Educational theories are often overlapping and dynamic; placing them in rigid categories may obscure important nuances (Green, 2019). For instance, dialogic and constructivist pedagogies share many features, as do holistic and critical approaches.

Additionally, the taxonomy lacks an explicit focus on epistemological and ontological underpinnings. Whilst it classifies teaching strategies and outcomes, it does not fully explore the deeper assumptions each paradigm makes about knowledge, reality and the learner’s role.

Lastly, some areas – such as environmental and technological pedagogies – are underdeveloped, reflecting their relatively recent emergence rather than a lack of importance. It also, arguably, overlaps with the philosophical and holistic as well as constructivist views.

Implications for teachers and TEACHER-researchers

For teachers, this taxonomy serves as a reflective tool to evaluate and diversify their teaching approaches. Rather than adhering rigidly to one paradigm, teachers can blend methods to suit their pupils’ unique contexts.

For teacher-researchers, this taxonomy opens the door to deeper questions about pedagogical paradigms and their underlying assumptions. It invites further exploration into how these paradigms influence pupil agency, curriculum design and teacher identity.

Final thoughts

I hope this tabulated taxonomy provides a useful framework for understanding the diverse landscape of contemporary pedagogy. By categorising educational theories into clear and accessible paradigms, it aims to support teachers navigating today’s complex teaching environments, especially given the abundance of competing theories. While no taxonomy can fully capture the richness of educational practice, this model is intended to promote clarity, encourage reflection, and lay the groundwork for more integrated and ethical teaching than that often presented by the narrower proponents of popular pedagogical paradigms.

As we continue to adapt to new challenges – technological, cultural and environmental – our pedagogical frameworks must remain as dynamic and inclusive as the pupils we serve.

References

Alanazi, A. (2016). A critical review of constructivist theory and the emergence of constructionism. American Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2, 1-8. DOI: 10.21694/2378-7031.16018

Alexander, R. (2008). Essays on pedagogy. Routledge.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32.

Biesta, G. (2023). Pedagogy, education, and flourishing: Beyond the science of teaching. Educational Theory, 70(3), 493–507.

Bloom, B. S. (1984). Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals. Longman.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review, 31(1), 21–32.

Christodoulou, D. (2014). Seven myths about education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315797397

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Kappa Delta Pi.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). Bloomsbury.

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Green, B. (2019). Taxonomies in education: The good, the bad, and the future. Journal of Educational Technology, 20(4), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.20849/jed.v5i2.898

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Kehl, J., Krachum Ott, P., Schachner, M., & Civitillo, S. (2024). Culturally responsive teaching in question: A multiple case study examining the complexity and interplay of teacher practices, beliefs, and microaggressions in Germany. Teaching and Teacher Education, 152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104772

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

Lee, J. H., & Chen, Y. (2020). Integrating taxonomy with AI in digital learning environments. Computers & Education, 157, 103985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103985

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 1–9.

Mercer, N. (2000). Words and minds: How we use language to think together. Routledge.

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children (M. Cook, Trans.). International Universities Press.

Cui, R., & Teo, P. (2020). Dialogic education for classroom teaching: a critical review. Language and Education, 35(3), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2020.1837859

Sweller, J. (2016). Cognitive load theory, evolutionary educational psychology, and instructional design. In D. C. Geary & D. B. Berch (Eds.), Evolutionary perspectives on child development and education (pp. 291–306). Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29986-0_12 Thompson, A. (2024), Rethinking Subjectification: On the Limits of Biesta’s Educational Theory. Education Theory, 74: 371-388. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12650

Picture credit: Giulia Forsythe via Flickr (used under a Creative commons Licence).