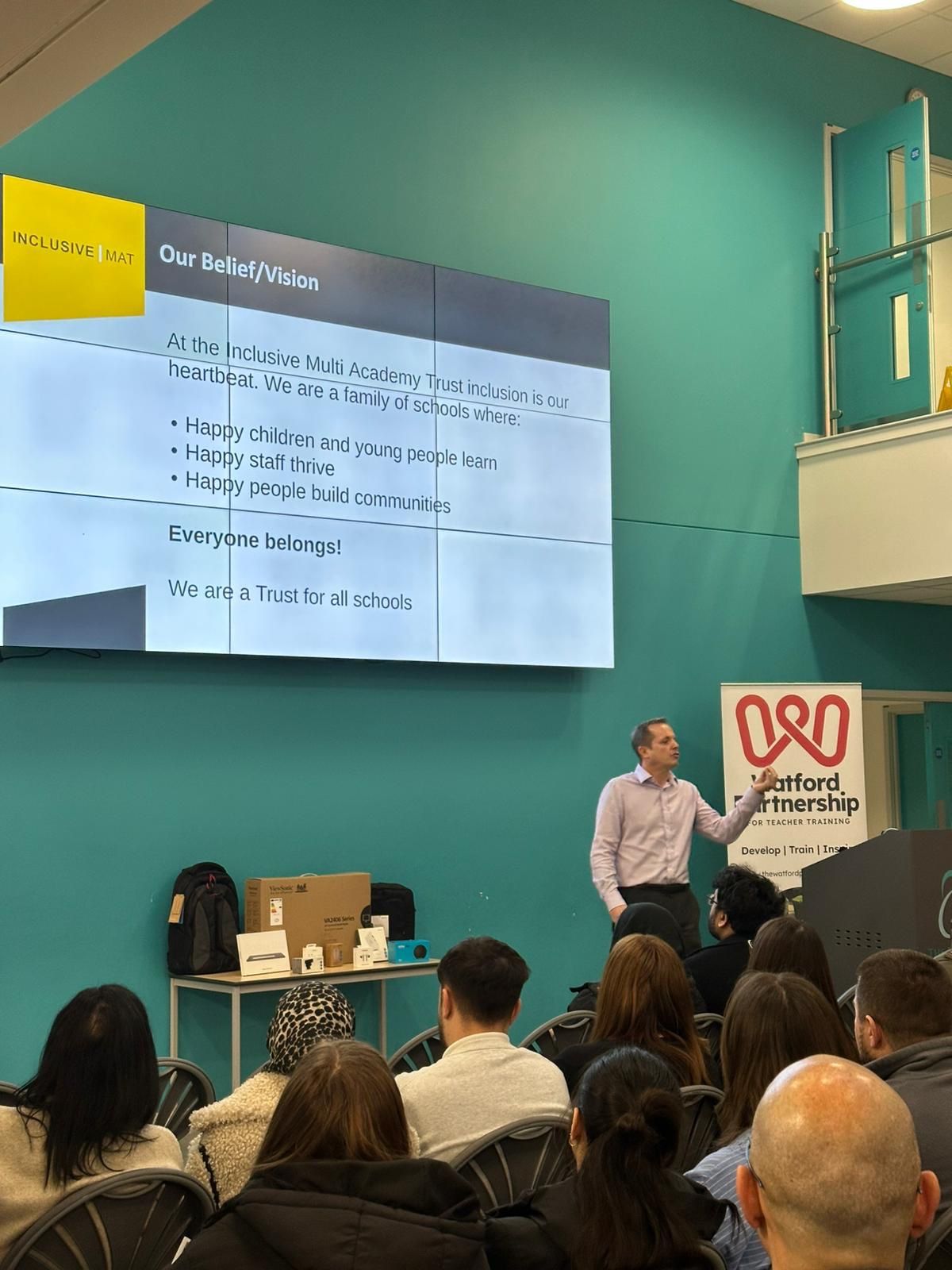

January’s TeachMeet at The Reach Free School, which attracted over 200 external attendees from 22 different schools, marked an important moment for professional learning within and beyond the Watford Partnership for Teacher Training (WPfTT). As a first iteration, it successfully demonstrated the power of teacher-led, peer-driven professional development (CPD) to share practical wisdom, foreground professional voice and foster a genuinely pluralistic approach to ‘what works’ in education. In contrast to more hierarchical or top-down models of CPD, as well as the often generic ‘research says’ approach associated with some external training providers, the TeachMeet format positioned teachers not simply as recipients of knowledge, but as legitimate generators, interpreters and critics of evidence and practice.

TeachMeet as a model of effective professional learning

The decision to run a TeachMeet, rather than a more formal conference or centrally directed training session, was a deliberate one. Research into effective CPD consistently emphasises relevance, collaboration, professional agency and sustained dialogue as key conditions for meaningful teacher learning (Cordingley et al., 2015; Opfer & Pedder, 2011). TeachMeets align strongly with these principles. Their short, focused presentations and marketplace stalls enable practitioners to share context-sensitive approaches that have emerged from real classrooms, whilst allowing colleagues to interrogate, adapt and selectively adopt ideas rather than comply with externally mandated initiatives or feeling pressured to follow trends in ‘best practice’.

Empirically, teacher-led professional learning communities have been shown to increase professional self-efficacy, pedagogical coherence and morale (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018). Importantly, they also redistribute epistemic authority. Teachers’ experiential knowledge is treated as a form of evidence, not an anecdote to be discounted. In this sense, TeachMeets enact what Cochran-Smith and Lytle (2009) describe as ‘knowledge-of-practice’, where professional learning is constructed through inquiry, dialogue and shared problem-solving.

The WPfTT TeachMeet exemplified this approach. The programme deliberately blended mini-keynotes with an expansive best-practice marketplace, encouraging both collective attention and informal, dialogic learning. This structure reflects research suggesting that professional learning is most impactful when it combines structured input with opportunities for sense-making and professional conversation (Timperley et al., 2007). Particularly notable was the deliberate inclusion of both primary and secondary colleagues, as well as two specialist providers, which enriched discussion, disrupted phase-specific silos and enabled ideas to be translated across age phases in thoughtful and nuanced ways.

Mini-Keynotes: Ideas with depth and applicability

The mini-keynotes demonstrated the intellectual breadth and practical depth that teacher-led CPD can offer. Topics ranged from inclusion and belonging to cognitive science, technology, leadership and wellbeing. Crucially, these were not abstract exhortations but grounded accounts of how theory intersects with classroom reality, whether in early phonics instruction or in GCSE and post-16 contexts.

The Best Presentation award, as voted for by attendees, went to Martyn Essery with his talk titled Stoicism’s Greatest Hits. The popularity of this session speaks to a growing appetite for frameworks that support teacher wellbeing without lapsing into superficial ‘resilience’ narratives. Drawing on Stoic philosophy, the presentation foregrounded locus of control, perception and action, concepts that resonate strongly with psychological research on stress, agency and cognitive appraisal (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). That this session emerged as a narrow winner also reflects the quality and diversity of the other presentations. Feedback indicated that many participants found the decision difficult, suggesting a high baseline of value across sessions.

Other mini-keynotes reinforced this sense of applied scholarship. James Roach’s work on inclusive practice foregrounded belonging, dignity and visibility, closely aligning with research on inclusion and pupil identity. Lipi Miah’s powerful exploration of ‘why names matter most’ drew explicitly on sociological and psychological evidence around belonging and microaggressions, whilst grounding this research in deeply human classroom experience. Laura Juniper’s presentation on generative AI offered a balanced and professionally responsible account that acknowledged both opportunity and ethical complexity, particularly in relation to reading, literacy and curriculum coherence. George Pritchard-Rowe’s examination of lesson delivery tools moved beyond surface-level technology debates to engage with cognitive load, attention and instructional design, whilst Jonathan Tyack and Nicola McEwan’s work on non-positional leadership challenged traditional hierarchies of influence by asserting that leadership is enacted through practice rather than title.

Collectively, these sessions illustrated that evidence-informed practice is not about uniformity, but about informed professional judgment exercised in context. The presence of both primary and secondary presenters strengthened this message, as ideas were continually reframed through questions of transferability, developmental appropriateness and system coherence across phases.

Some of the mini-keynote speakers: James Roach, Martyn Essery, and Laura Juniper.

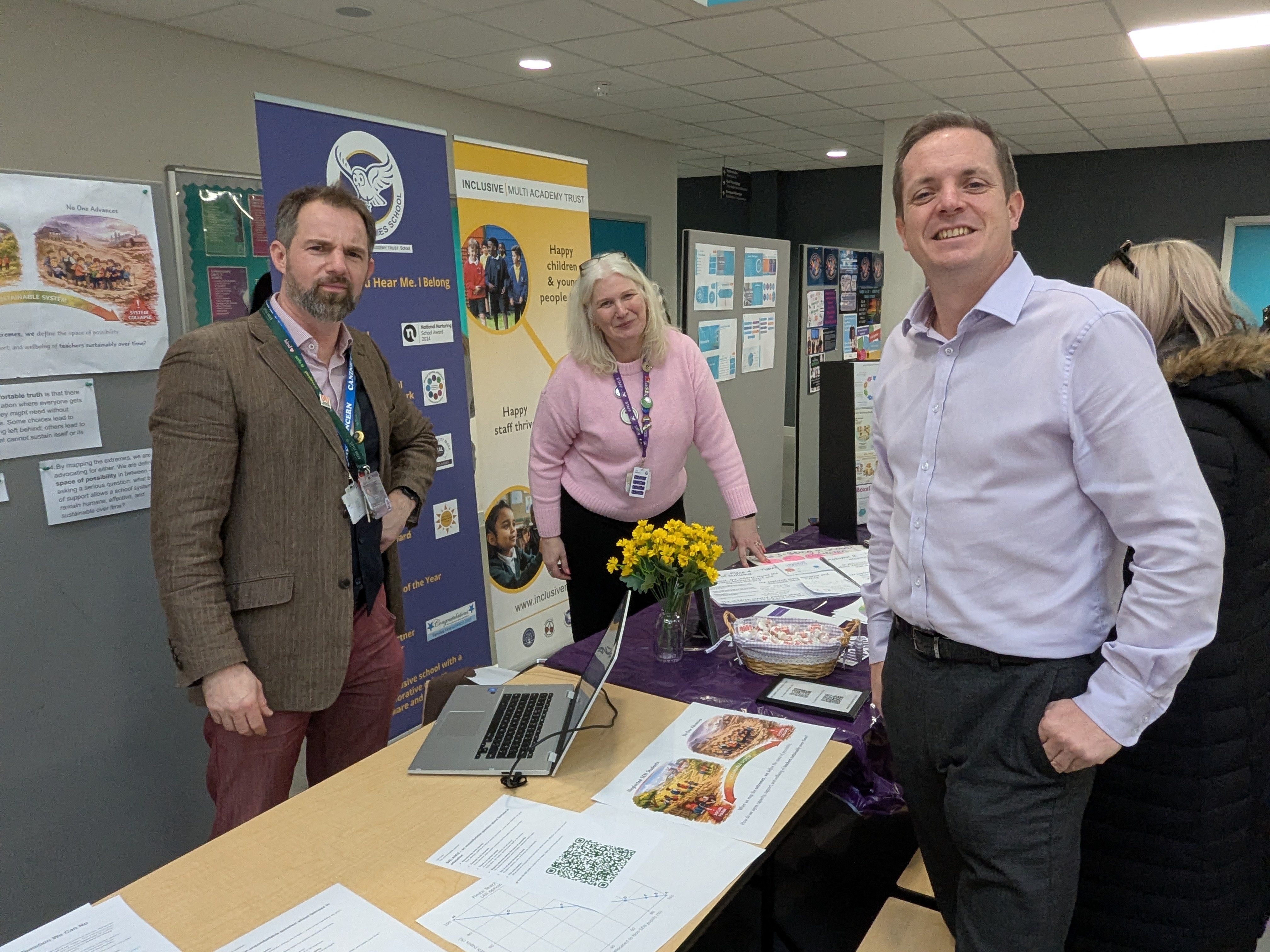

The Marketplace: Practical wisdom and situated expertise

The TeachMeet marketplace further embodied democratic CPD in action. With over thirty stalls spanning primary and secondary phases, participants were able to engage with colleagues whose work reflected diverse school contexts, pupil populations and professional priorities. This plurality matters. Research cautions against ‘one-size-fits-all’ models of evidence use, noting that decontextualised solutions often fail to translate into sustainable practice (Biesta, 2007).

The ‘Best Primary Stall’ award was won by Nicola Furey, whose stall focused on a Nurture Approach. This recognition reflects the continued salience of relational and trauma-informed approaches in schools. That this stall resonated so strongly suggests a shared professional recognition that learning cannot be separated from wellbeing, particularly in primary contexts where relational foundations are paramount.

The ‘Best Secondary Stall’ award went to Amber Richardson, whose stall, Resource Design: Top Tips and Ideas, highlighted the value teachers place on practical and applicable strategies. Its popularity suggests that colleagues particularly value approaches grounded in lived classroom experience rather than abstract prescription. Such ‘craft knowledge’ is often undervalued in policy discourse, yet studies of teacher expertise consistently show that adaptive decision-making and thoughtful resource design are central to effective teaching (Shulman, 1987).

As with the presentation award, voting for stallholders was extremely close. Attendee comments repeatedly noted the difficulty of choosing, underscoring both the quality of the contributions and the appetite for collaborative professional exchange across phases. The stalls showcased a wide array of ideas, interventions and examples of practice, including, for instance, approaches to retrieval, the development of metacognitive skills, the application of phonics, outdoor learning, the embedding of British Values within the curriculum and role-play-based learning for neurodiverse learners, among many others.

Top right (centre): Primary stall winner, Nicola Furey. Bottom right: Secondary stall winner, Amber Richardson.

TeachMeets, evidence and democratic professionalism

A persistent tension in education policy concerns the interpretation of ‘evidence-based’ or ‘what works’ approaches. Whilst evidence-informed practice is of considerable value and teachers would be amiss to ignore it, critics argue that overly technocratic models risk narrowing professional autonomy and reducing teaching to compliance with prescribed methods (Biesta, 2015). The WPfTT TeachMeet offers a compelling alternative, one that is evidence-informed rather than evidence-mandated.

By enabling teachers to draw on research, theory and classroom data whilst also sharing narrative, reflection and professional judgment, the TeachMeet fits in well with models of democratic professionalism (Sachs, 2001). Again, teachers are not positioned as passive consumers of research but as active participants in its interpretation and enactment. This is particularly important given evidence that sustainable improvement is most likely when teachers feel ownership over change processes (Fullan, 2016).

This format also lends itself particularly well to mentoring and informal professional support. TeachMeets create low-stakes spaces in which early career teachers, new leaders and more experienced colleagues can interact as peers, enabling mentoring relationships to emerge organically rather than through formal assignment. Research consistently highlights the importance of professional networks in teaching, noting that access to collegial relationships, informal advice and shared professional capital is associated with improved practice, resilience and retention (Coburn, Russell, Kaufman & Stein, 2012; Daly, 2010). Practical considerations also matter. Offering incentives such as refreshments, and where possible making attendance free, helps to reduce barriers to participation and signals that professional learning is a collective, collegial endeavour rather than an additional burden.

Colleagues sharing practice and networking alongside our Sixth Formers, who provided the catering.

Some tips for planning a TeachMeet or similar event

There is no single right or wrong way to organise a TeachMeet, and the vast majority that I have attended, particularly those that incorporate stalls and displays which colleagues can visit at their own pace, have worked well. The WPfTT TeachMeet was a general, uncontroversial celebration of all things teaching and school-related, but such events could equally be more subject-, phase-, or thematically centred, provided there is sufficient interest and attendance.

- Keep it teacher-led and voluntary: The success of a TeachMeet depends on professional trust. Voluntary participation encourages authenticity, generosity and credibility. It avoids the compliance associated with mandated CPD.

- Design for brevity and focus: Short presentations or stall like displays respect teachers’ time and attention, reduce performativity and foreground ideas that are clear, purposeful and transferable.

- Allow time for informal professional dialogue: Build in generous opportunities for networking, mentoring and conversation. Much of the most meaningful professional learning occurs in these informal spaces. A ‘marketplace of ideas’ is ideal for this.

- Ensure cross-phase and cross-role representation: Including both primary and secondary colleagues, and teachers at different career stages, enriches discussion and supports the transfer of ideas across contexts.

- Make the event accessible: Where possible, keep attendance free and reduce practical barriers. Simple incentives such as refreshments signal that colleagues’ time and participation are valued.

Final thoughts

The WPfTT TeachMeet 2026 was more than a showcase of good ideas. It was a practical enactment of teacher-led, democratic and evidence-informed professional learning. Through its format, content and ethos, it amplified teacher voice, respected professional expertise and created space for plurality rather than prescription. The closeness of the award voting speaks not only to the quality of individual contributions, but to the collective strength of the professional community.

If this TeachMeet is, as hoped, the start of an annual tradition, even twice-yearly (as Watford Boys are planning on a Summer TeachMeet), it offers a powerful model for CPD that is intellectually serious, professionally respectful and rooted in the realities of classrooms. In an educational landscape often dominated by top-down narratives of ‘what works’, the WPfTT TeachMeet stands as a reminder that some of the most robust evidence for improvement emerges when teachers are trusted to lead.

As the event organiser, I was grateful to my colleagues, internal and external, for supporting the event, and to my line manager, Richard Booth, for encouraging it and for allocating the time and resources it required.

References

- Biesta, G. (2007). Why “what works” won’t work: Evidence-based practice and the democratic deficit in educational research. Educational Theory, 57(1), 1–22.

- Biesta, G. (2015). Good education in an age of measurement. Routledge.

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance. Teachers College Press.

- Coburn, C. E., Russell, J. L., Kaufman, J. H., and Stein, M. K. (2012). Supporting sustainability: Teachers’ advice networks and ambitious instructional reform. American Journal of Education, 119(1), 137–182.

- Cordingley, P., et al. (2015). Developing great teaching. Teacher Development Trust.

- Daly, A. J. (2010). Social network theory and educational change. Harvard Education Press.

- Fullan, M. (2016). The new meaning of educational change (5th ed.). Routledge.

- Hargreaves, A., & O’Connor, M. T. (2018). Collaborative professionalism. Corwin.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- Opfer, V. D., & Pedder, D. (2011). Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Review of Educational Research, 81(3), 376–407.

- Sachs, J. (2001). Teacher professional identity. Journal of Education Policy, 16 (2), 149-61.

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22.

- Timperley, H., et al. (2007). Teacher professional learning and development. OECD.

Thanks Andrew, Steve Kolber has been organizing similar TeachMeets in Melbourne https://sites.google.com/view/teachmeetmelbourne/home

LikeLike