Introduction

As part of my EdD research, I have been exploring the Department for Education’s (DfE) Early Career Framework (ECF, 2019) using a combination of critical discourse analysis (CDA) and critical realism (CR). These theoretical lenses help unpack the ways in which the framework constructs teacher professionalism, embeds power relations and aligns with broader educational policy trends. Essentially, I am interested in how the ECF is shaping early career teachers’ (ECTs) pedagogical practice and professional identities.

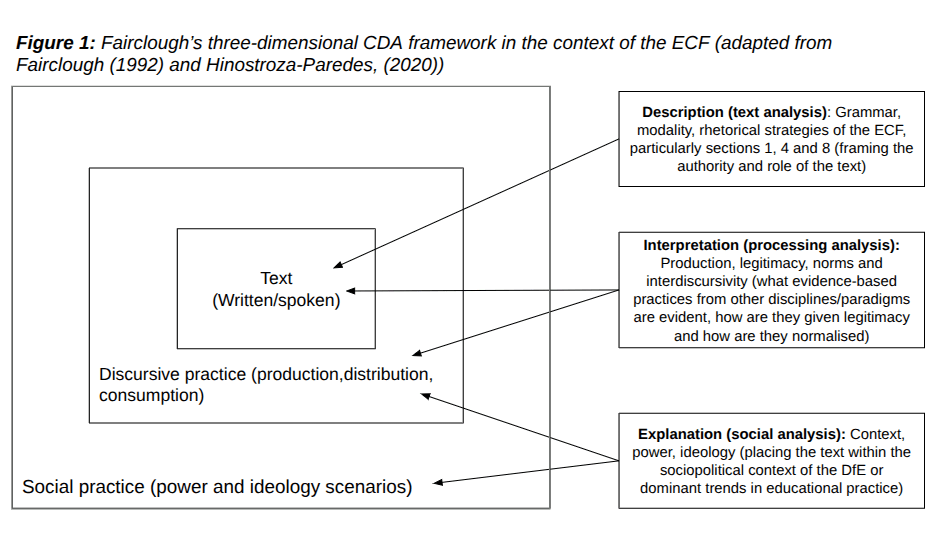

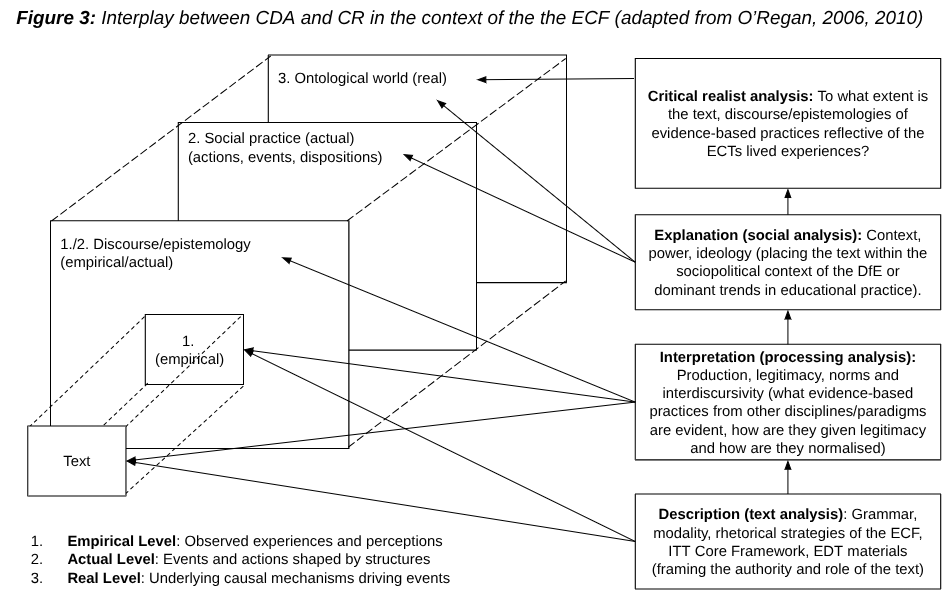

In this blog, I discuss how Norman Fairclough’s (1992) CDA model, Roy Bhaskar’s (1975) stratified ontology of CR, and David Scott’s (2010) structuration approach can be used to analyse the ECF. The diagrams I reference illustrate the interplay between these perspectives and provide a structured way to critically engage with education policy.

So far, they have helped consolidate my thinking and methodological approach to this study, although I am now considering Fairclough’s (2018) ‘CDA as dialectical reasoning’ as an alternative.

Fairclough’s three-dimensional model and the ECF

One of the most useful tools for analysing policy discourse is Fairclough’s (1992) three-dimensional model of CDA (Figure 1). This model helps break down how the ECF operates at different levels:

- Text (description) – At this level, I examine the linguistic features of the ECF, such as grammar, modality and rhetorical strategies. The way the framework is written constructs particular professional identities for teachers, positioning them within a structured, evidence-based paradigm.

- Discursive practice (interpretation) – This focuses on the production, distribution and consumption of the ECF. It explores how the framework legitimises certain pedagogical approaches and aligns itself with wider discourses of teacher effectiveness and professional development.

- Social practice (explanation) – At this macro level, the ECF is analysed within the wider sociopolitical landscape. This includes examining how power and ideology operate within the framework, particularly in relation to recent education reforms that emphasise standardisation, accountability and performativity.

By applying Fairclough’s CDA model, I can critically interrogate how the ECF constructs knowledge and authority within the teaching profession, revealing the implicit assumptions and power dynamics embedded in its discourse.

The interplay between CDA and critical realism

While CDA is effective for examining discourse, it needs a deeper ontological foundation to fully account for the structures and causal mechanisms influencing educational policy. This is where Bhaskar’s critical realism (CR) provides an additional layer of analysis (Figure 2).

Bhaskar’s stratified ontology distinguishes between three levels of reality:

- Empirical level – What we can directly observe, such as teachers’ experiences of the ECF.

- Actual level – The events and actions influenced by policy structures, including how the ECF is implemented in schools.

- Real level – The underlying causal mechanisms driving these events, such as the agentic, embodied and institutional forces shaping ECTs engagement with the ECF.

Applying CR alongside CDA allows me to move beyond simply analysing the text of the ECF to investigate why certain discourses emerge and how they reflect deeper social structures. It also prompts important questions:

- To what extent does the ECF reflect the real lived experiences of ECTs?

- Are there structural constraints that limit how ECTs engage with the framework?

- How does the DfE’s policy agenda shape the knowledge that is valued within teacher training?

By integrating CR with CDA, I can explore these questions in a way that moves beyond discourse analysis alone.

Scott’s Structuration Approach: Linking Structure and Agency

A key limitation of both CDA and CR is that they can sometimes prioritise structure over agency. David Scott’s (2010) structuration approach helps address this by acknowledging the dynamic relationship between institutional structures and individual agency (Figure 3).

Scott identifies several overlapping structures that shape teacher identity and practice within the ECF:

- Embodied Structures – Policy constraints, workload expectations and accountability measures.

- Discursive Structures – The dominant ideas and beliefs about what makes an ‘effective teacher’.

- Agency Structures – Teachers’ past experiences, professional relationships and career trajectories.

- Institutional Structures – The specific school policies, training norms and expectations shaping ECTs’ engagement with the framework.

- Social Markers – Factors such as class, gender and ethnicity, which influence teachers’ experiences in different ways.

By mapping these structures, Scott’s approach reveals the tensions between policy mandates and individual autonomy. In Figure 3, the solid lines suggest areas where causal mechanisms conflict with the ECF, while the dotted lines indicate areas where policy aligns with teachers’ lived experiences.

This perspective is particularly useful in understanding how teachers navigate the constraints of policy while exercising their professional agency. It highlights the complexity of policy implementation and reminds us that teachers do not simply passively accept policy prescriptions—they engage with, resist and reinterpret them in different ways.

Final Thoughts: Why This Matters for My Research

Studying the ECF through the combined lens of CDA and CR theory has deepened my understanding of how policy is constructed, disseminated and enacted. It also raises important critical questions for my EdD research:

- Does the ECF truly empower teachers, or does it reinforce existing power hierarchies?

- How do teachers interpret and engage with the framework in practice?

- Are there structural barriers that limit the agency of early career teachers?

These are the kinds of questions that a purely descriptive policy analysis would fail to address. By drawing on Fairclough, Bhaskar and Scott, I can critically engage with policy discourse while also accounting for the material conditions shaping its implementation.

As I continue with my EdD research, I hope to explore these issues further by gathering empirical data from teachers themselves, examining how their lived experiences compare to the ideological assumptions embedded within the ECF.

This blog represents an ongoing reflection on my theoretical approach—one that, I hope, will contribute to broader discussions on teacher policy, professional identity and educational reform.

References

- Bhaskar, R. (1975). A realist theory of science. Routledge.

- Department for Education (DfE). (2019). Early Career Framework. London: DfE.

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

- Fairclough, N. (2018). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- O’Regan, J. P. (2006). Critical discourse analysis and critical realism: Challenges and conflicts. In G. Weiss & R. Wodak (Eds.), Critical discourse analysis: Theory and interdisciplinarity (pp. 220–238). Palgrave Macmillan.

- O’Regan, J. P. (2010). Critically examining the ideological structures of discourse. Critical Discourse Studies, 7(2), 141–154.

- Scott, D. (2010). Education, epistemology and critical realism. Routledge.

- Stutchbury, K. (2022). Critical realism: An explanatory framework for small-scale qualitative studies or an ‘unhelpful edifice’? International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 45(2), 113–128.